Shock is a serious condition that occurs when there is inadequate supply of oxygen to meetthe needs of the tissues. Lack of oxygen to the peripheral tissues cause the tissues to stop functioning properly and can quickly lead to death.

There are 4 types of shock that occurs in children:

Hypovolemic Shock

The most common cause of shock in children is hypovolemia and is mostly due to fluid loss. Hypovolemia can be identified by decreased preload, increased or normal contractility and increased afterload. The following are the causes of hypovolemic shock:

| Causes of Hypovolemic Shock |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Signs of Hypovolemic Shock |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Management of Hypovolemic Shock

Nonhemorrhagic Hypovolemia

The key to management of nonhemorrhagic hypovolemia in children is the infusion and retention of fluids. Proper and timely administration of fluids is crucial in treating hypovolemic shock and can quickly lead to recovery. Infusion of 20 ml/kg boluses of isotonic crystalloid will be effective to treat a child with hypovolemic shock and up to 3 boluses can be given if the patient doesn’t improve.

Hemorrhagic Hypovolemic Shock

For hemorrhagic shock start with fast infusion of isotonic crystalloid in boluses of 20 mL/kg and give up to 3 boluses for a total of 60 mL/kg. For every 1 mL of blood loss, it is important to supplement 3 mL of crystalloid for the initial treatment. If the patient remains unresponsive consider Packet Red Blood Cells (PRBCs) transfusion in 10 mL/kg boluses. There are no pharmacological interventions that are effective for either hemorrhagic or nonhemmorrhagic hypovolemic shock. Therapy includes fluid dosage, identifying the cause of volume loss and correcting metabolic imbalance.

Distributive Shock

Distributive shock occurs when there is improper distribution of blood volume and there is decreased organ and tissue perfusion. Distributive shock can be identified as normal or decreased preload, normal or decreased contractility and afterload that is variable. There are 3 types of distributive shock:

The 2 key treatment options for distributive shock are: restoration of hemodynamic stability and identification and control of infection.

Septic Shock

Septic shock causes a decrease in tissue perfusion and oxygen due to infection by certain organisms or endotoxins. Septic shock can be identified by decreased preload, normal to decreased contractility and an afterload that is variable. The following are signs of septic shock:

| Signs of Septic Shock |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Management of Septic Shock

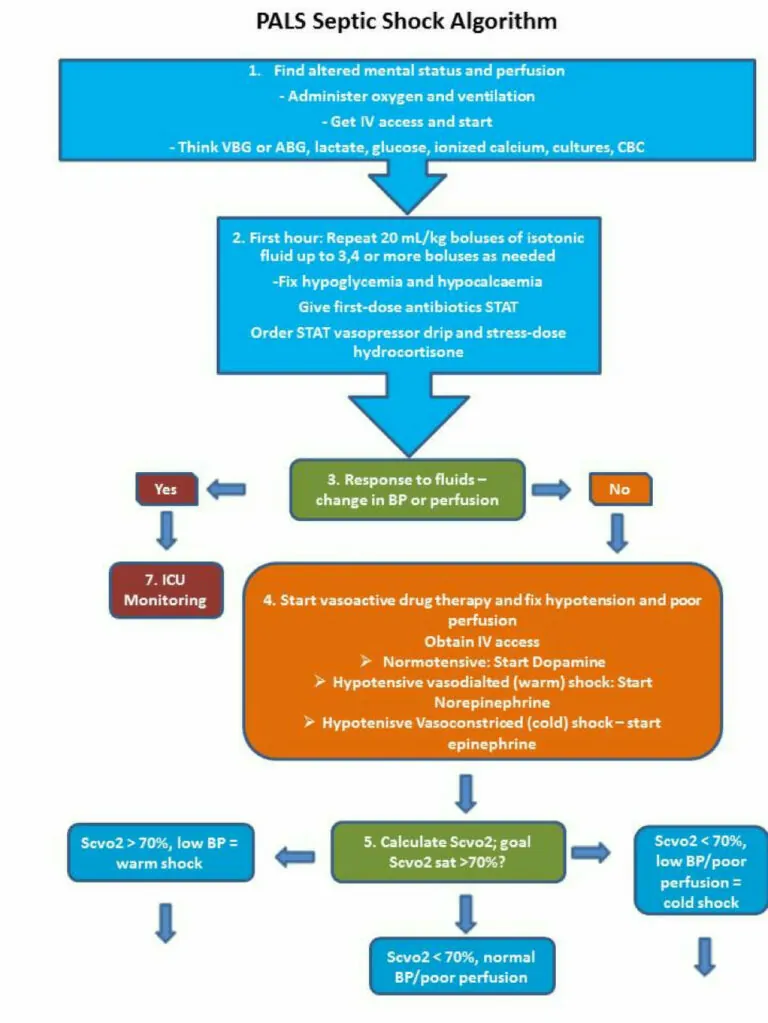

The following description shows the proper methods in treating septic shock:

The following is an algorithm showing the management of septic shock in pediatric patient:

Anaphylactic Shock

Anaphylactic shock results in vasodilation and low blood pressure with bronchoconstriction causing the child to stop breathing immediatly. Anaphylaxis occurs due to reaction to a certain good, drug, toxin, vaccine, plant, poison or antigen. Signs and symptoms of this shock include:

| Signs and Symptoms of Anaphylactic Shock |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Management of Anaphylactic Shock

The primary goal in the treatment of anaphylaxis is to target problems associated with bronchoconstriction and vasodilation.

Management of Cardiac Arrest

The most important component in the management of cardiac arrest is activating the EMS and implementing high-quality CPR continuously. There are different steps in order to treat a child with VT/VF and those with asystole or PEA.

Neurogenic Shock

Disruption of the autonomic pathway of the spinal cord due to head or spine injury results in hypotension, bradycardia and loss of sympathetic nervous system signals to the smooth muscle in the vessel walls.

Management of Neurogenic Shock

or

Cardiogenic Shock

Cardiogenic shock results when the ventricles of the heart fail to function properly and there is inadequate circulation of blood throughout the body. Cardiogenic shock can be identified by a variable preload, decreased contractility and an increased afterload. The causes and signs of cardiogenic shock include:

| Cause of Cardiogenic Shock |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Signs of Cardiogenic Shock |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Management of Cardiogenic Shock

Obstructive Shock Obstructive shock results when there is obstruction of the great vessels of the heart and results in impaired cardiac output. Proper management

of obstructive shock includes correction of cardiac output and tissue perfusion. There are 4 types of obstructive shock:

Cardiac Tamponade

Cardiac tamponade occurs when there is accumulation of fluid, blood, pus or air in the pericardium and is usually due chest trauma, hypothyroidism, pericarditis, cardiac surgery, cancer and myocardial rupture. Some signs and symptoms of cardiac tamponade include:

Management of Cardiac Tamponade

The key to management of cardiac tamponade is the removal of fluid from the pericardial sac (pericardiocentesis) and proper administration of fluids for quick improvement of the child.

Tension Pneumothorax

Tension pneumothorax is accumulation of gal or air in the pleural cavity and can be caused by a tear from injured lung tissue, or chest trauma. Some signs of tension pneumothorax include:

| Signs and Symptoms of Tension Pneumothorax |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Management of Tension Pneumothorax

Treatment of tension pneumothorax includes needle decompression and thoracotomy of chest tube placement. The physician or trained professional should insert an 18-20 gauge- over- the needle catheter on the top of the child’s 3rd rib for successful dissemination of air.

Ductal-Dependent Lesions

Ductal dependent heart lesions are birth defects of the heart that are seen in the first weeks of life. The ductal dependent lesions include ductal dependent for pulmonary blood flow and one for systemic blood flow. The ductal lesions for pulmonary blood flow are seen without shock but with cyanosis in the child. The left ventricular outflow tract obstructive lesion is seen with shock in the first 2 weeks of life when the patent ductus arterisous closes. Signs of ductal dependent for systemic blood flow include:

| Signs of Ductal-Dependent Lesions |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Management of Ductal-Dependent Lesions

Management of ductal dependent lesions is by administration of prostaglandin E1 which restores ductal patency by vasodilation. Other management techniques include support by oxygenation, administration of inotropic agents to improve contractility, fluid administration to fix cardiac output and correction of metabolic imbalances.